Collaborative Editing in CoCalc: OT, CRDT, or something else?

This paper about collaborative editing is on Hacker News today.

I also recently talked with Chris Colbert about his new plans

to use a CRDT approach to collaborative editing

of Jupyter notebooks.

This has caused me to be very curious again about how CoCalc’s collaborative editing is related to the many algorithms and research around

the problem in the literature.

The Collaborative Editing Problem

Protocols for collaborative editing are a venerable problem in computer

science, and there are probably over a hundred published

research papers on it. The basic setup, going back three decades, is that sync algorithms are supposed to have three properties, which I’ve stated in simplified

plain language below:

- 1. convergence: everybody’s document looks the same if they all take their hands off the keyboard for a while,

- 2. causality preservation: if somebody else’s change is applied to your local version of the document, then you make a change, then your change is always applied after their change (in 1).

- 3. intention preservation: the effect of applying a change operation is the same for everybody, as when it was initially done. (Yes, this is vague; it’s much harder to make

precise than 1 and 2.)

CoCalc has 1, of course; without that you’ve got nothing.

CoCalc has 2, when people’s clocks are synced, because all patches you’ve applied have timestamp less than now (=time when making the patch).

CoCalc does NOT have 3, for some meaning of 3. Patches are applied on a “best effort basis”. So instead of our changes being “insert the word ‘foo’ at position 7”, they are more vague, e.g., apply this patch with this context using these parameters to determine Levenshtein distance between strings. With intention preservation, if the operation is “insert word ‘foo’ at position 7”, definitely that’s exactly what happens whenever anybody does it (‘foo’ will appear in the document) – it does not depend at all on context. With diffmatchpatch patches (which we use in CoCalc), the effect of the patch depends very much on the document you’re applying the patch to. If there is insufficient context, then ‘foo’ might not get inserted at all.

Similar remark apply to how I designed the structured object sync in CoCalc, which is used, e.g., for CoCalc Jupyter Notebooks;

it also applies patches on a best effort basis.

This is a protocol that in theory has all of 1-3. Of course there

are many, many specific versions of OT. The hard part is ensuring 3,

and it can be complicated. The problem to be solved makes sense,

and it can be done. The details (and implementing

them) are certainly nontrivial to think about conceptually…

There’s many academic research papers on OT,

and it’s implemented (well) in many production

systems.

In OT, the data structure that defines the document is simple (e.g., just a text string), and the operations are simple, but applying them in a meaningful way is very hard. This paper on HN that I mentioned above argues that OT

is much more popular in production systems than CRDT.

CRDT = commutative replicated data type

This also does 1-3. It sets everything up so the

data structure that defines the document is very complicated

(and verbose), but it’s always possible to merge documents in

a consistent way. What is difficult gets pushed to different

places in the protocol than OT, but it’s still quite hard,

and there are subtle issues involved with any non-toy implementation.

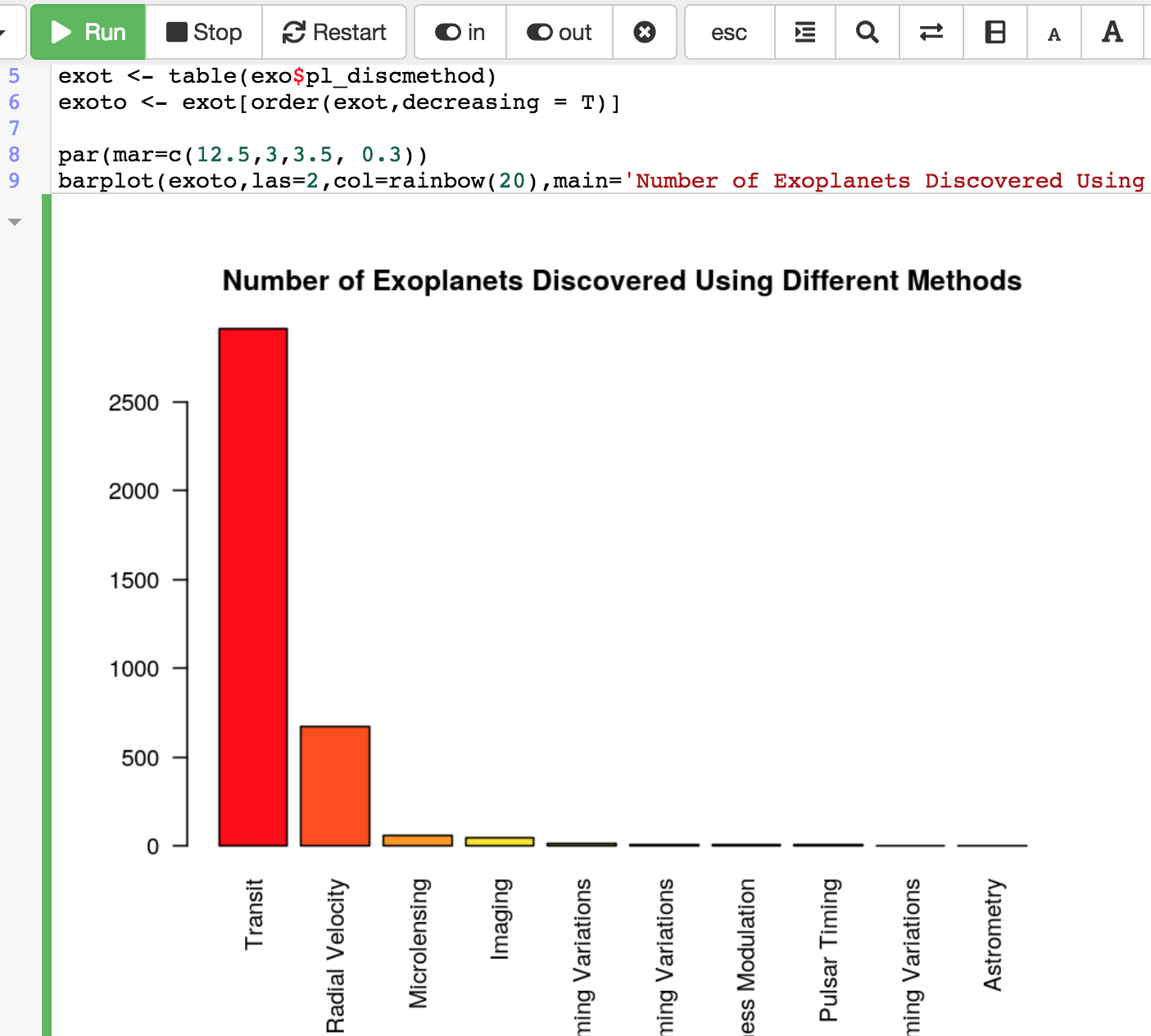

What about CoCalc’s approach…?

CoCalc’s text editing does synchronization as follows. Each

user periodically computes a timestamped patch, then broadcasts

it to everybody else editing the same file. When patches arrive,

each user computes the current state of the document as the

result of applying all patches in timestamp order.

If everybody stops editing, then they all agree on the same

document.

This protocol satisfies 1 and 2, but not 3. The reason is that

patches are applied on a best-effort basis using the diff-match-patch

algorithm. For example, a patch made from deleting a single letter

in a document can, when applied to a different document end

up deleting multiple letters (or none). Basically, CoCalc replaces

all the very hard work needed for 3 that OT and CRDT’s have with a notion of applying patches on a “best

effort” basis. The behavior is well defined (because of the timestamps),

but may be surprising when multiple people do simultaneous nearby

edits in a document.

The paper says:

“There are two basic ways to propagate local

edits: one is to propagate the edits as operations [12,38,50,51,73]; the other is to propagate the edits

as states [13]. Most real-time co-editors, including those based on OT and CRDT, have adopted

the operation approach for propagation for communication efficiency, among others. The operation

approach is assumed for all editors discussed in the rest of this paper”.

Here [13] is N. Fraser’s paper on Differential Sync. This was the sync

algorithm in the first version of CoCalc, and was the inspiration for

what CoCalc currently does.

In CoCalc, the data structure that defines the document is simple (just a text string, say), and the operations are less simple (computing diffs, defining patches), and applying them in a meaningful way is

somewhat difficult (it’s what the diffmatchpatch library does).

This approach is very easy to think about and generalize, since it

is self contained and a local problem. After all, I mostly described the algorithm in a single paragraph above!

In CoCalc, we compute diffs of arbitrary documents periodically,

much like how React.js DOM updates work.

This seems to not be needed in OT or CRDT, which instead track the

actual operations performed by users (i.e., type a character,

delete something).

Computing diffs has bad complexity in general, but very good

complexity in many cases that matter in practice (that’s

the trick behind React). Diffs involve observing state periodically, rather than tracking changes.

OT and CRDT really are solving a much harder problem than we solve. This is similar to how git uses the trick of “assume sha1 hashes don’t collide” to solve a much easier problem than the much harder problems other revision control systems like Darcs solve.

An Example in which CoCalc violates the intention preservation requirement

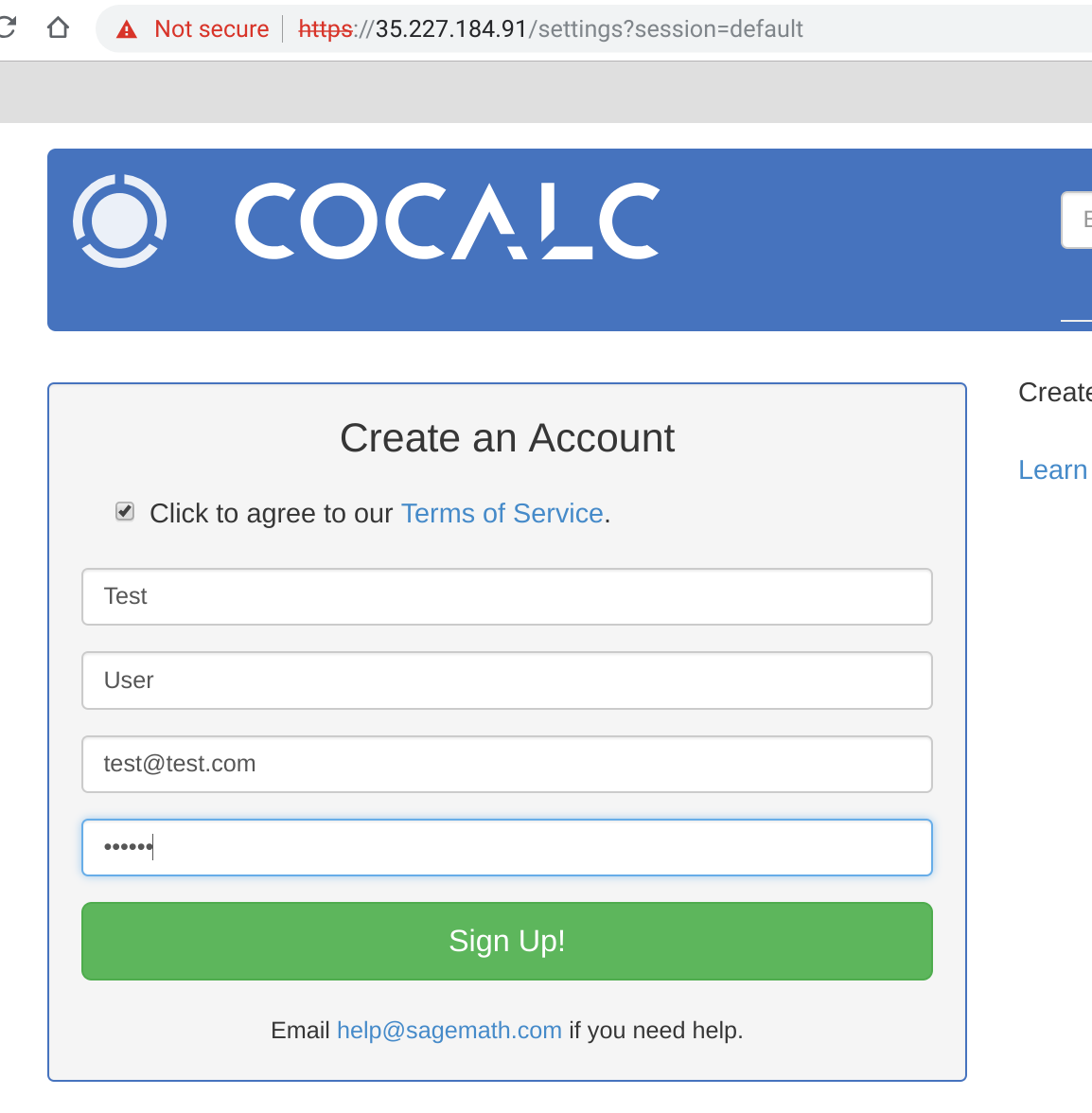

There is a nice example to illustrate how CoCalc fails for this third “user intention” requirement. This is called “the TP2 puzzle”. You can try the following in both CoCalc and Overleaf (which probably does some OT algorithm):

- Type in some blank lines, then “abcd”, then blank lines

- Open three windows on the doc you’re editing.

- Disconnect your Internet

- In each of the three window, make these changes, in order:

- abcxd (put x after c)

- abycd (put y before c)

- acd (delete b)

- Reconnect and watch. The experts agree that the “correct” intention preserving convergent state is “aycxd” (which overleaf produces), but CoCalc will produce “acxd”.

I do NOT consider this a bug in CoCalc – it’s doing exactly what is implemented, and what I as the author of the realtime sync system

intended.

The issue is that the patch to delete “b” has “a” and “cd” as surrounding

context, and if you look at how diffmatchpatch patch application works, this is a case where it just deletes everything inside the context.

Evidently, Google Wave also had issues with TP2 because fully implementing OT is…

“… hard! In fact, almost all published algorithms that claim to satisfy TP2 have been shown to be flawed.”

More details…

The “famous” TP2 puzzle for CoCalc ends up like this (in at least 1 of the 6 possibilities!).

Start with

then add an x and a y on either side of b, and delete b.

In one order, end up with

The patches are:

[[[[0,"--\n\n\nabc"],[1,"x"],[0,"d\n\n\n\n\n"]],5291,5291,14,15]]

[[[[0,"---\n\n\nab"],[1,"y"],[0,"cd\n\n\n\n\n"]],5290,5290,15,16]]

[[[[0,"\n---\n\n\na"],[-1,"b"],[0,"cd\n\n\n\n\n"]],5289,5289,16,15]]

Applying the “delete b” patch, also deletes the y:

apply_patch([[[[0,"abc"],[1,"x"],[0,"d"]],5291,5291,14,15]], 'abcd')

(2) ["abcxd", true]

apply_patch([[[[0,"ab"],[1,"y"],[0,"cd"]],5290,5290,15,16]], "abcxd")

(2) ["abycxd", true]

apply_patch([[[[0,"a"],[-1,"b"],[0,"cd"]],5289,5289,16,15]], "abycxd")

(2) ["acxd", true]

Looking at the source code of diffmatchpatch, this is just what DMP does. If there is a lot more badness and the strings are bigger, it’ll refuse to delete. It really is a sort of “best effort application of patches” with parameters and heuristics; no magic there.